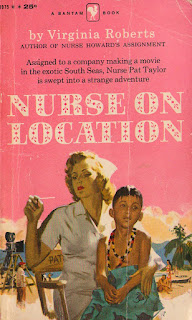

When Five Star

Pictures decided to shoot Island Intrigue on location on a beautiful Pacific island, Nurse Pat Taylor was put in

charge of the health of the glamorous stars. To young Pat, this was a dream

come true. But barely had Pat set up her tiny hospital when she met a strange

young American doctor, John Stewart, mysteriously hiding himself in this remote

tropic outpost, and found that by giving succor to a dying native girl, she had

broken an implacable tribal law and aroused the primitive anger of the native

chieftain. Here is an adventure which might happen to any nurse if she was

nurse on location.

GRADE: C+

BEST QUOTES:

“Who but a movie star

could walk right up and ask a man for a date? Here she was reluctant even to

phone Catherine’s friend, Dr. John Stewart. It did seem aggressive.”

“A fascinating woman. Beautiful. Mysterious. Everything that

intrigues a man.”

“Suddenly she thought of the scene at Los Angeles Airport,

just before the plane left. He had clutched his wife and two children as though

he thought he was never going to see them again. He must have some sort of

complex.”

“What a real, down-to-earth attitude movie people have.”

“Young women. What a batch of champagne bubbles you all

are.”

“Most people think that an anesthetist is some jerk who

flips a vacuum over your nose and yells to breathe deep.”

“Later that afternoon, when Pat returned to the hut, she

found Vivienne weeping with as much fervor as though she were being paid $5,000

a week to emote.”

“You’ve got to stop worrying about other people, and start

relaxing. If you don’t, you’re apt to swell up like a blimp.”

“His specialty is mental disturbances. He might take one

look at you and pop you into a sanitarium.”

“Haven’t you learned yet a girl has to flirt a little if she

wants to catch a man?”

“If it’s a career you’re after, always remember it’s never

more important than a woman’s appearance.”

“It’s never good technique to keep a man waiting—too long.”

“Advice is cheap when you’re giving it out.”

REVIEW:

Pat Taylor has completed her nurse’s training and is about

to embark on her graduate studies at Johns Hopkins to become a nurse

anesthetist, but she has a few months to kill before school starts in the fall.

Through the intervention of a former preceptor, she has scored a dream job:

traveling to Fiji for the summer with a film crew that is making a major motion

picture. She’s been asked to drop in on the preceptor’s old friend, John

Stewart, who is a doctor doing some unspecified research into “mental diseases

among people far away from civilization.” Needless to say, Pat is instantly

smitten with Dr. Stewart: Though their telephone conversation is purely small

talk and lasts less than a page, it results in his politely asking her to

dinner, and after hanging up, she thinks, “I shall look forward to tonight more

than any other night I can remember.” Though their date confirms Pat’s opinion

of him as “the most fascinating man I’ll ever meet,” his career is put forth as

something of a mystery: Though her friend has told her what he is studying, he

doesn’t really talk about it (but she doesn’t ask, either), and she starts jumping

to all sorts of wild conclusions: “Who are you? What are you? Why are you? Was

he running away from something?”

As it is soon revealed, this propensity for wild flights of

imagination is one of Pat’s major characteristics. Shortly after she moves into

her clinic, a local boy carries in a very sick young native woman, who dies

hours later of perforated appendicitis. Pat overhears the crew discussing how

“those dumb natives are trying to put the blame for that girl’s death on poor

Pat. … No telling what they’ll do.” From then on, the poor Fijians, previously

described as warm, welcoming, and civilized, are viewed by Pat with increasing

hysteria: They’re ferocious, angry, “mean and secretive and suspicious”—words that really could be used to describe Pat’s own attitude. Again and again, she’s

freaking out because some local person happens to be behind her or is

looking at her when she walks down the street. On virtually every other

page there’s some nasty thought of hers about how when they speak to each other

in their native tongue they are saying something “ugly and obscene” and how at

any moment “the natives might strike.” If they ever did, I’d be inclined to

jump in and help.

She voices her paranoid opinions to John Stewart, who

manages to stay seated for the remainder of their date. Later, he tells her he

loves her—but that he has no right to woo her. Pat’s delusions immediately take

flight again: “Was he engaged? Married? What was it that suddenly caused a

mountain to spring up between them? Why should he choose to remove her, at the

flick of an eyelash, from his life?” Someone has been seriously skipping their

meds. Eventually her time in the Pacific winds to a close, and there’s nothing

but a luau between her and the plane ride home when she is asked to tend to

another native child, this one a mere toddler, with an infected foot wound. She

angrily agrees to see the child, and we are told that “here again was a mercy

call she could not refuse and be true to her profession”—though it’s hard to

see how Pat’s overwhelming fear and brusque treatment of the patient and his

family could be called mercy.

Two days later, John Stewart shows up, for the first time

since he told Pat he loved her but couldn’t see her any more, to let her know

that the child had an allergic reaction to the antibiotics she had given him

and had almost died. He helpfully reveals that it had taken every bit of his

skill to convince the local chief not to “take matters into his own hands. Or

did you know what those drums meant? The drums were for you, and it wasn’t a

celebration in your honor.” Thanks, John. But now the natives love Pat,

showering her with gifts and flowers when she's out and about, and we’re

treated to a ghastly description of the natives as “a paradoxial people,

teetering between savagery and civilization,” again, a description better suited for Pat herself. All that’s left is for Pat to be anointed princess of the island at the

luau—the villagers all drop to their knees and shout, “Long live the white

princess!” as, wearing a crown made of ferns and flowers, she ascends a podium to her throne—and we are hard-pressed to retain our lunch.

But wait, there’s more! Guess who is the white king of the

island? Guess who relents and asks Pat to marry him? Guess who tells her, “You

can forget about being a stuffy anesthetist. I’m the one who needs you”? Guess

who instantly chucks her career aspirations and sighs, “No girl was a real

woman until she possessed the love of the right man”? Guess who finally loses

her struggle and throws up?

You’d think I’d learn by now that if there is ever anyone

brown on the cover of one of these books, the interior is almost guaranteed to

be filled with hateful racism. It’s really too bad, because if the prejudice

had been edited from this book, it would have been quite pleasant: The writing

is generally enjoyable, the author has a fine sense of humor, and the minor characters, anyway, are well-drawn and interesting. Unfortunately, the plot is

thoroughly saturated with bigotry, not just against the Fijians but also, at the end, women as well. If you can

manage to take an anthropologic view, examining the relics of a bygone era with

a detached eye, you might get some enjoyment from this book, but the author

just doesn’t make it easy.

No comments:

Post a Comment